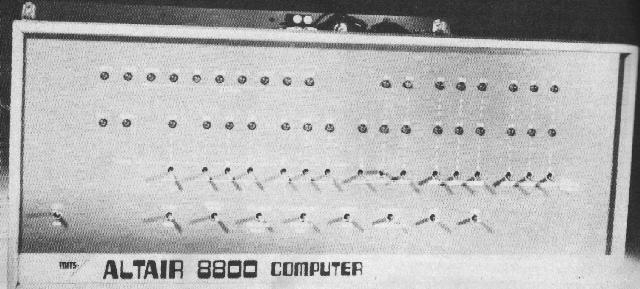

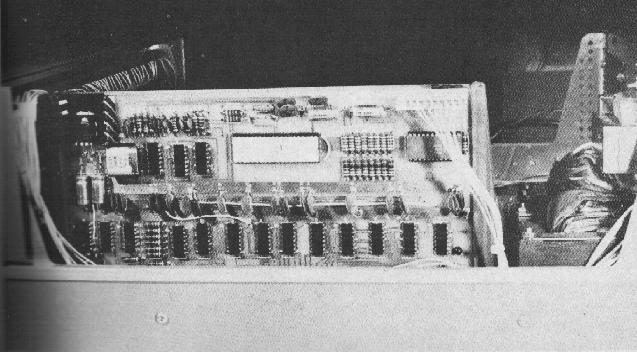

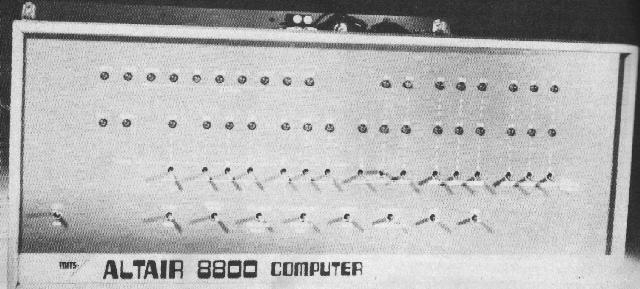

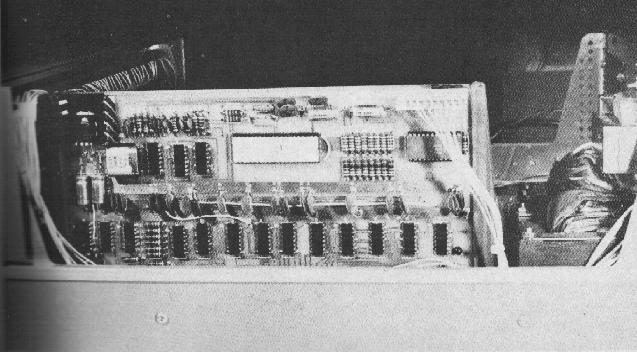

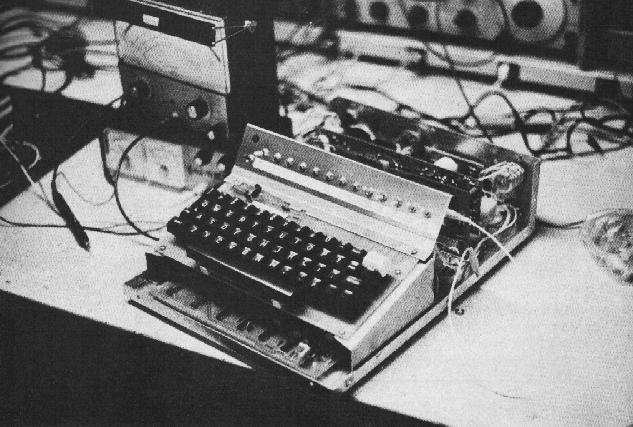

The Altair 8800 ...

and a look inside.

| Computers Are Here - Are You Ready ? Originally written by Wayne Green in october 1975 |

The Three Basics

There are three parts to a computer system ... the central processing

unit, cleverly called a CPU, the gadget which costs the most money and

which does most of the work ... an input/ouput device such as a teletype

... and some sort of memory for the CPU to keep things on file when it

is not actively working with them.

IC technology has been raising havoc with CPU prices, dropping them

in large increments every few months. The latest chips such as the Intel

8008, 8080, National PACE, IMP-16, and Motorola M6800 have spawned a breed

of miniature CPU which is so low in cost that it has made the hobby computer

a practicality. The first large quantity production of CPU's using the

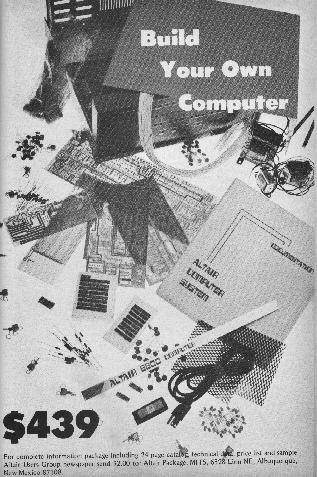

new series of microprocessor chips was put out by MITS in January 1975

... Their Altair 8800.

This sold for $439 in kit form and $621 assembled and tested ... about

one tenth the price of previously available minicomputer units.

RGS Electronics and Scelbi Computer System had been producing computer

kits before this using the Intel 8008 chip, but these were not as well

publicized and the 8008 chip has more limitations than the 8080, which

is used in the Altair.

More and more CPU kits are becoming available ... such as the recently

announced Godbout system using the National PACE chip ... this holds a

lot of promise for a lot of computer at a ridiculously low price.

Another new one is Sphere, available in kit or assembled form in the

same basic price range of $500-$600 with enough built-in memory to do some

work.

There are two basic forms of memory required ... one in CPU to permit

it to do work ... and one outside for longer term use. The internal memory

stores operating program instructions and things retrieved from the larger

memory which have to be used by the CPU. Practically speaking, the larger

the internal memory of the CPU, the faster your computer system can operate.

For instance, if you had a record of all the stations you've ever contacted

in the main memory and you wanted to sort through for one particular call,

it would be easier to find if your CPU could grab a thousand stations out

at one time and check them against the call you need instead of checking

maybe ten at a time. You'd find the record you want one hundred time faster.

But, alas, memory cost money, and a happy medium as to be struck between

what you want and what you can afford. You can get along with 4K of memory

... That's actually 4096 bytes, where a byte is 8 bits of memory, the amount

needed to represent a letter or number. Memory costs about 4 cents per

byte (1975), but it will be coming down.

Long term memory units have been coming down in price too, though it

is still possible to buy a brand new Ampex 40 megabyte disk system for

$24,000 if you like to pay this price and get into that sort of scene.

More in the amateur end are some of the soon to be seen floppy disk systems

which will be selling in the $500 range and which will provide about 250K

of memory on each disk. The disks are a lot like phonograph records and

can be changed quickly.

One of the simplest and the least expensive memory systems involves

the audio cassette recorder, and many hobbyists seem to be working in this

direction. It is a little slow, but it is extremely cheap and you can have

a lot of memory that way. The standard for using them is a familiar one,

with the two RTTY audio frequency shift tones being

used.

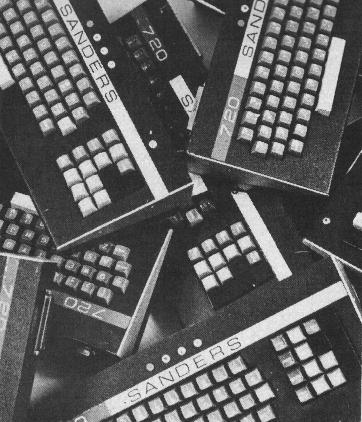

Keyboards from Sanders: Running rampant. |

Even the input/output situation is changing rapidly. Of course you can buy an old teletype machine for $50 to $100 and it will work quite well. You might even want to go to a faster and more modern machine, if you can promote one at less than the price of a good used car. The more usual system now is to put together a video display terminal and work from that. These are available in kit form for around $150 to $250 and are a cinch to put together. The Southwest Technical video display generator costs $175 in kit form and it can be put together by a twelve year old. The keyboard that goes with this one runs another $40 and works like a champ. Or you may want to shop around for a surplus keyboard for the same or a slightly lower price ... Most of them have ASCII output and this is all you need to hook things together for a working system. |

For complete information package including 24 pages catalog, technical data, price list and sample Altair User Group newspaper send $2.00 to: Altair Package, MITS, 6328 Linn NE, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87108. |

Uses

Once you have your CPU, memory I/O up and working, you then have to decide what you want to do with the system. You may want to use it to keep track of stations you've worked, with little bits of information about them for recall on the video screen (any television set will provide the video part of the terminal for you). You may want to catalogue your record collection of your book library ... Or perhaps articles in the ham magazines. If you are into RTTY you realize that your computer system is the main part of the RTTY station. You can program it to send a 60 words per minute, either from the keyboard or from any material you have in the memory ... and receive the same way, printing it out (and memorizing the stuff, if you want) on your screen. Perhaps you prefer CW ... so program the computer to convert the ASCII letters into appropriate CW characters ... select the speed you prefer ... and type away as fast as you like for several hundred words. Your computer can also decipher incoming CW for you and print it on the screen. There probably will be a good deal of 50 wpm CW around in the future as computer-assisted ops work each other. Your checkbook? No strain, many hobbyist are using their system for keeping their bank accounts in order. If you have a small business of your own you may want to apply some of the computer power into it ... inventory ... account receivable ... mailing list ... things like that. |

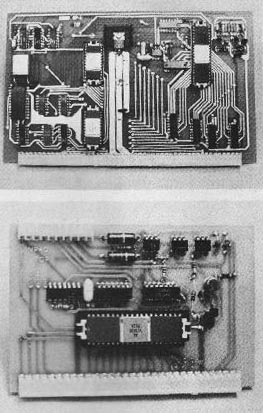

CPU and Serial Interface boards from South-West Tech. |

Learning about computers

An unfortunate number of the books which have been published with the purported aim of helping you to learn about computers are just plain terrible. The fact is that the rank newcomer to computers is in for a very difficult time. The magazines (which the exception of BYTE, which sort of resulted from this situation) are written for professionals and have little of interest or value to a beginner. Little is written for the experimenter, the circuit designer, or the programmer ... with most magazines being devoted to the business end of the computer field. 73 author Pete Stark has written an interesting introduction to computer programming which is scheduled to be reprinted by Tab Books ... watch for an announcement of that one. The Lancaster TTL Cookbook is fine for hardware fans ... published by Sams at $8.95. |

If you've read about binary numbers you know that 000 = 0, 001 = 1,

010 = 2, 011 = 3, 100 = 4, 101 = 5, 110 = 6, 111 = 7. Thus using this notation

a binary number such as 01 011 111 would be written 137.

Got it? That's called octal notation (base 8).

The Intel 8080 chip and the Mits Altair 8800 as a bunch of instructions

built into it when you get the unit. This tells you that, if you set the

first memory to 072, this will instruct the CPU to pick up whatever number

you have in a specific part of the memory and put it into a small memory

unit called register A ... this is all done inside the 8080 chip. When

we push the "deposit" switch this puts the 072 into the first memory position.

Next we set up the switches for 200 ... this is the place where we will

put the number we want to add. We push the "deposit next" switch and this

puts the 200 into the second memory position. After consulting the instructions

again we set up 107, which means move what we had in register A to register

B. "Deposit next" takes care of that.

Now we pick up the second number ... the one we want to add to the

first. 072 (deposit next) says move to register A the contents of what

we say next ... 201 (deposit next). A 200 instruction tells the chip to

add A to B. Then an 062 tells the chip to move that some to whatever location

we say next ... we pick 202 and deposit that information. We end the operation

by telling the chip to jump back to 000 again and wait for further instructions.

Perhaps you can see why machine language is a back breaker and why everyone

wants to get programs which will enable them to merely type in something

simple like: A = 300, B = 5.3, C = A x B, PRINT C, END, RUN. There are

a great many computer languages ... something over 700 in current use ...

but a few have come into more popular acceptance such as RPG, COBOL, BASIC,

FORTRAN, and such. The most basic of instructions to the computer are usually

put in by means of punched tape or by cassette ... such sample programs

has assemblers, this is a lot faster than sitting there flicking bat switches

for each of the eight bits to load a program into a couple thousand memory

positions ... your fingers and patience would wear out. So would the switches

after a while.

If you get into this field you'll find that most of the computer languages

are relatively simple ... you just have to sit down for a few days and

work with them until you get the hang of the things and learn to correct

your mistakes ... and you'll make a lot of them. Programming is difficult

only because it is exacting - a computer does not forgive errors, it just

compounds them for you. It takes a lot of time and patience to beat new

trails ... so it is fortunate that user groups are proliferating to provide

exchanges of programs ... why keep on inventing the wheel, right?

I hope I haven't worried you about computers ... they are not very

expensive these days (1975) ... are getting cheaper ... and are an enormous

amount of fun to play with. Get cracking ... and as you conquer new territory,

make a chart for the rest of us and send the information to 73 and BYTE.